Paul Jackson: William Tyndale: Victoria Embankment Gardens

London has hosts of statues which generally become duller and more obscure to both the eye and the mind as the events and figures they commemorate become increasingly distant; unless, that is, they have the anarchic drama of Boadicea or the formal familiarity of Nelson's Column or Eros. The rest are the retired po-faced worthies of the past suffering the unwanted affection of pigeons.

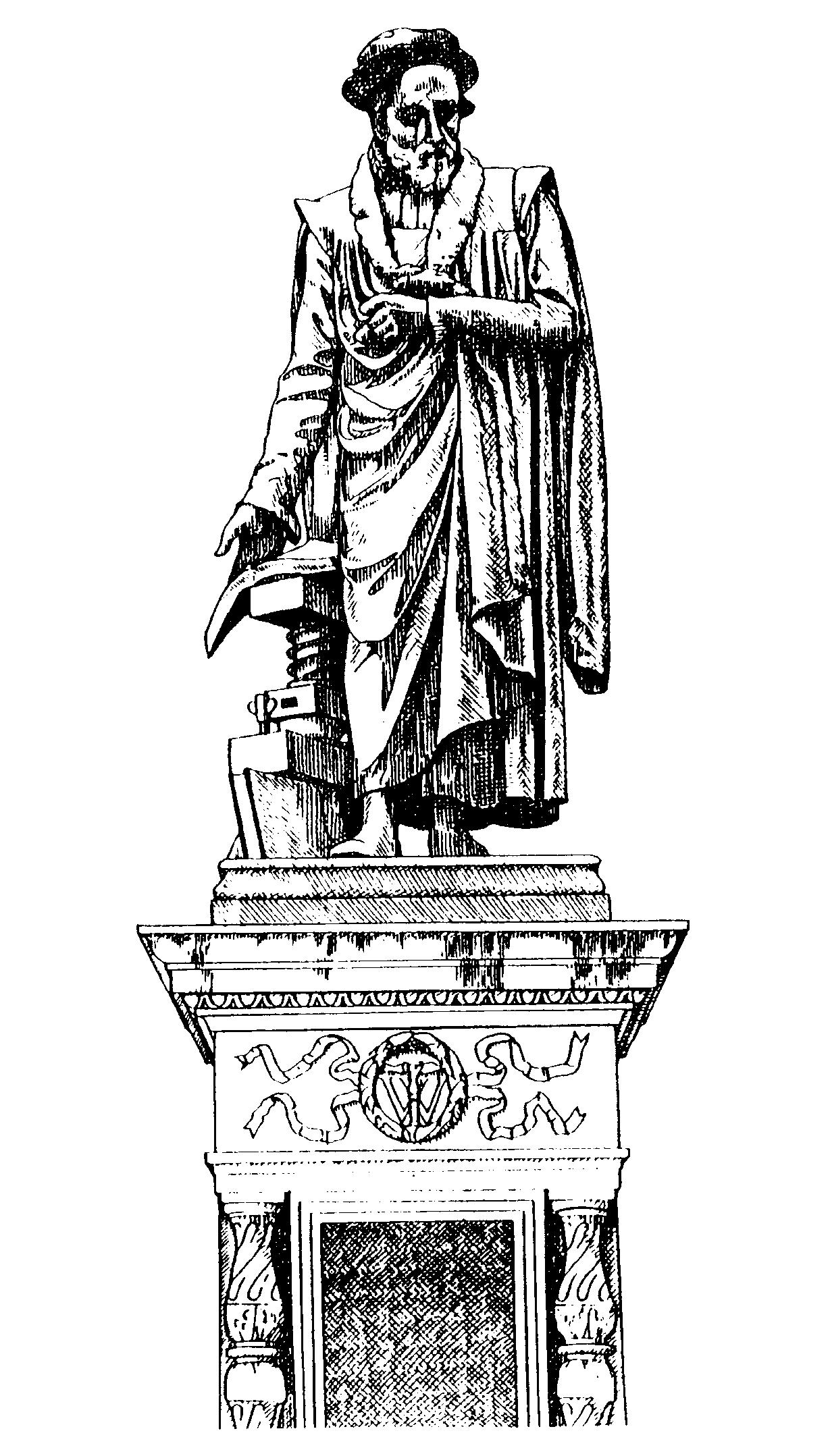

Tyndale has a statue too. It might seem rather tucked-away in the Victoria Embankment Gardens now, but in the 1880s the Embankment was a plush site following Bazalgette's massive reclamation works along the Thames finished in 1870. The sculptor was Sir Joseph Edgar Boehm who was considered "virtually the keystone of establishment sculpture during Victoria's reign."[1]

This bronze statue was unveiled on May 7th 1884 in token of the 80th anniversary of the British and Foreign Bible Society, and also being the 400th anniversary of 1484, the date that the bronze plaque beneath claims for Tyndale's birth.[2]

The statue is a fine one. Boehm's background in Vienna and the Continent brought to his work rather more vivid articulation "than the standard broad anodyne treatment that was the general rule in England, undercutting marble and modelling deeper for bronze thus producing a more varied effect of light and shadow..."' The stance is quite lively with some movement in Tyndale's frozen gesture towards his books that manages to be dignified without being pompous. There is a kind of how implied in the graceful turn and sweep of the body which in no way compromises the vertical accent necessary to this kind of monument.

The portrait is not entirely fanciful; it is based on the painting at Hertford College Oxford, but whereas that shows the writer interrupted from his work, this is in academic garb and with his attributes of books and printing press. I rather think that a seated, writing Tyndale might have made a good composition but it wouldn't have complemented its standing companion pieces, Outram and Bartle-Frere, in the garden layout. Certainly Boehm's most successful figure' is a seated one, the wonderfully restless Carlyle on Chelsea Embankment.

Blackwood comments that Boehm has "augmented the beard and softened the line of strain about the eyes"' that is apparent in the painting. Qualities of any face are hard to read, much less with such a healthy heard, but Boehm's attempt to convey Tyndale is very credible. He has maintained some of the evidence of the ravages of heavy study together with a convincing strength and mildness. Others might read it differently but I think they would agree that this lacks the complacency of the faces of so many Victorian statues.

|

| |

| William Tyndale | Boehm's statue of Thomas Carlyle |

Even the printing press beside him is a careful portrait of a sixteenth century one in the Antwerp Museum.[4] Within the haphazard arrangement of leaning books, it might suggest the sort of picturesque scenery that a gun carriage might lend to a posing general, but Tyndale's right hand binds it all into the composition and therefore into himself. You could easily imagine a child there or a beloved dog in its place. Simultaneously his left hand catches up the folds of robe to stop them brushing the delicately balanced book. Boehm's Tyndale with his books and press is in the tradition of church iconography; that of showing a saint in his or her full dress uniform, be it camels-hair apron or cope and mitre, with their appropriate accessories of sword, spiked wheel, grid-iron, or else a weighty tome, a hand-held cathedral or candle. Tyndale is shown in this tradition unlike his neighbours, the politician or soldier. John Blackwood is right when he says that the "statue is exceptionally skilful and impressive" but speaks little "about the pioneering courage of William Tyndale" [4]; however, if I'm right about the tradition evoked, personified heroism and fortitude (adored by the Victorians) is always silenced in the representation of saints who in altarpieces "cast their crowns" at the feet of the Saviour. Tyndale like the altar saints stands proudly by his books and press that were both his charge and the death of him. Even his gesture to the open hook cannot be read as the self-congratulation of a heroic thinker or writer but as a tender devotion to a text one could die for.

This statue is a successful work of art and faithfully does honour to Tyndale. I feel it ought to be better known and appreciated, especially as it also acts as a memorial, with the implication of remembering both the man and his work as a National treasure. This must have been the intention of The British and Foreign Bible Society who have shared the same zeal and energy, and I hope that they were pleased with it. I also hope that with a 200th anniversary approaching in 2004, they will find as good a way of celebrating. There is probably still some mileage in memorials to Tyndale.

NOTES

- Arthur Byron, London's Statues: A Guide to London's Outdoor Statues and Sculpture 1981 hardback

- Inscriptions:

William Tyndale

First Translator of the New Testament into English from the Greek.

Born AD 1484. Died a martyr at Vilvorde Belgium AD 1535.

(Texts: Psalm 119 vss 105, 130; 1 John 5 v 11)

The last words of William Tyndale were "Lord open the King of England's eyes." Within a year afterwards a bible was placed in every parish church by the King's command.

The following public bodies have each contributed £100: British and Foreign Bible Society, Oxford University, Cambridge University, Sunday School Union, British and Foreign Sailors Society, Young Men's Christian Association, Polytechnic Young Men's Institute, Birmingham, Cheshire, Dorsetshire, Kent, Liverpool, Hon Company of Grocers, St Mary of Quebec Chapel, Proprietors of the Quiver, Court of Common Council of the City of London, Belfast — Ireland. - Benedict Read, Victorian Sculpture 1982 hardback, paperback

- John Blackwood, London's Immortals 1989 hardback

| |

| William Tyndale |