The new translation which was to become the New International Version of the Bible was begun in 1968, after discussions which had started as far back as 1956 about the necessity for and feasibility of another translation. The cost was underwritten by the International Bible Society. Work was done from the start on both the Old and New Testaments. The New Testament was published in 1973, and the whole Bible in 1978, containing some revisions of the earlier New Testament. The translators and editors came from all denominations, with theologians of diverse traditions, so that the translation would as much as possible reflect the original text, not particular theological beliefs. The team, did, however, have to have a belief in the inspiration of the Bible, in line with the policy statement of the feasibility committee which had met in Illinois in 1965: ‘It is the sense of this assembly that the preparation of a contemporary English translation of the Bible should be undertaken as a collegiate endeavor of evangelical scholars.’[1]

The method of translation was a follows:[2]

Initial translation team

Each book of the Bible was assigned to a group of from three to five scholars, who produced a fresh translation by working from the original languages.

Intermediate Editorial Committee

An Intermediate Editorial Committee then reviewed the team translation, checking it carefully with the Hebrew, Aramaic or Greek, and improving the English Style. The International Editorial Committees were composed of from five to seven editors, many of whom had served at the team level on one or more of the Bible books. These Intermediate Editorial Committees changed from session to session and this cross-fertilisation gave freshness and unity to the translation.

General Editorial Committee

A General Editorial Committee then reviewed the work of the Intermediate Editorial Committee, carefully checking it again with the original languages for accuracy and striving to improve it stylistically. These committees also had from five to seven members, some of whom had worked on both the initial teams and the Intermediate Editorial Committees.

Stylists and Critics

The translation was then sent to all translators, to stylist and to other critics (not only to specialists but also to people from all walks of life) for their review and suggestions.

Executive Committee (of Committee on Bible Translation)

The Executive Committee, a permanent body of fifteen members, held itself responsible for presenting to the International Bible Society a satisfactory translation. Hence it subjected every translation of the General Editorial Committees to a further close review. Taking into account all the suggestions of the stylists and critics and doing its own independent checking of the original languages, it made improvements on the General Editorial Committee translation.

(The top speed of the Intermediate and General Editorial Committees and the Executive Committee was five verses and hour).

Final Stylistic Review

Then the revised translation was sent out once again to two select English stylists for a final check.

Executive Committee's Final Reading

Moving much more swiftly this time, the Executive Committee reviewed the

suggestions of the two stylists to see whether they were in harmony with

the original languages and with the other stated goals of the translation.

(Steps 6 and 7 were omitted for the New Testament. Instead, five years after the New Testament was printed in 1973 a modest revision was made on the suggestions that had been submitted by the translators, other Biblical scholars, stylist and the general public.)

Although the translators had avoided as much as possible an American style of English, there were inevitable phrases and spellings which are not used this side of the Atlantic and Professor Donald Wiseman of the University of London who had participated in the translation programme was asked to chair a group who Anglicised the text.[3]

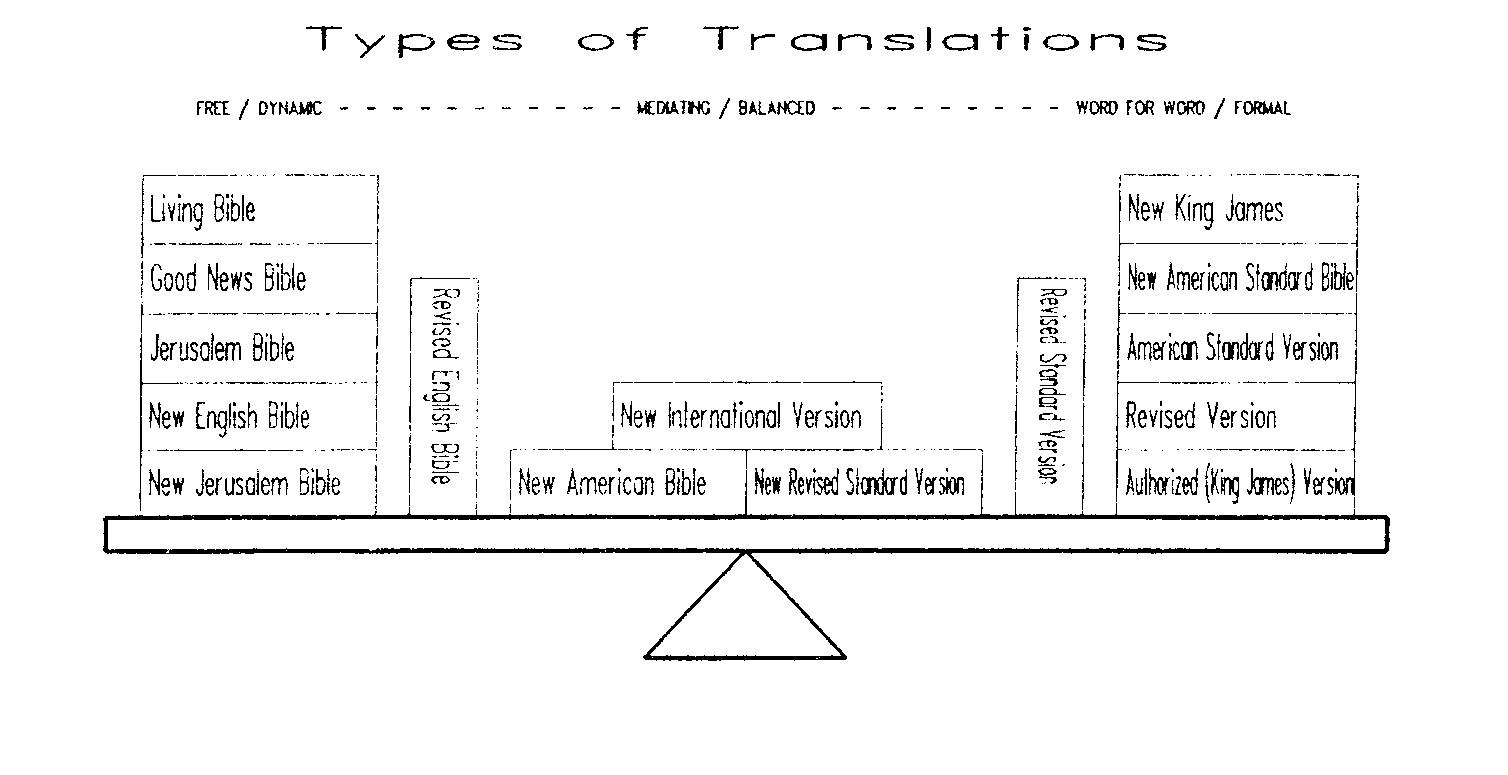

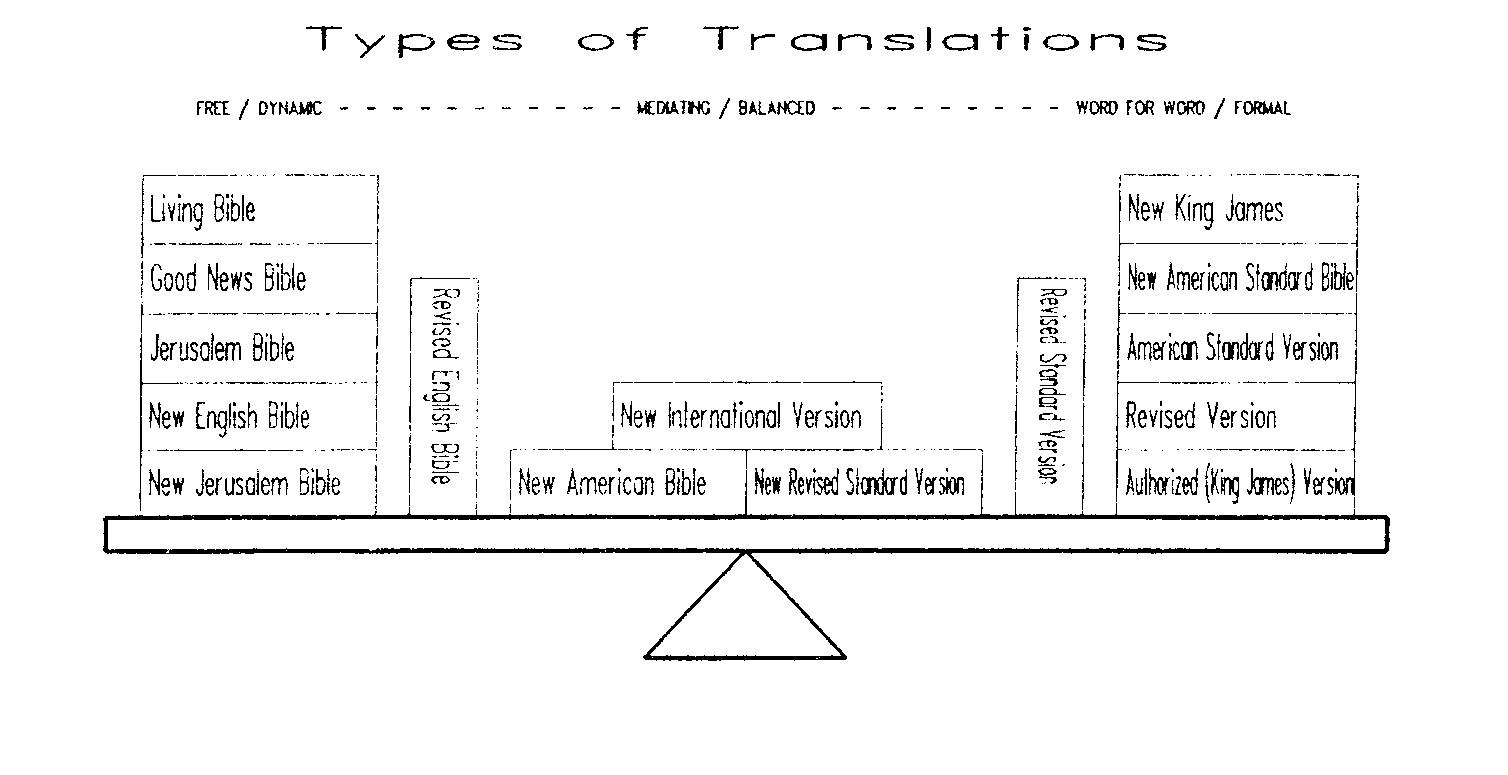

The writer of The Story of the New International Version outlines the principle which guided the translation: ‘...an eclectic one with the emphasis for the most part on a flexible use of concordance and equivalence, but with a minimum of literalism, paraphrase, or outright dynamic equivalence. In other words, the NIV stands on middle ground — by no means the easiest position to occupy.[4]... There is a sense in which translation is like a seamless garment; in it, method and style are woven together. Though language suitable for both private and public reading has been a basic aim of the NIV, this has had to be sought for in the light of the literary and stylistic diversity within the Bible. Faithful translation requires different stylistic levels: to a real extent it must reflect the character of the original. When the original is beautiful, its beauty must shine through the translation; when it is stylistically ordinary, this must be apparent.’[5]

I give here the two Creation stories, to compare with JB and NJB quoted in my previous article.

In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth. Now the earth was formless and empty, darkness was over the surface of the deep, and the Spirit of God was hovering over the waters.

And God said, ‘Let there be an expanse between the waters to separate water from water.’ So God made the expanse and separated the water under the expanse from the water above it. And it was so. God called the expanse ‘sky’. And there was evening, and there was morning — the second day.

Genesis 2.4b reads:

When the Lord God made the earth and the heavens — and no shrub of the field had yet appeared on the earth and no plant of the field had yet sprung up, for the Lord God had not sent rain on the earth and there was no man to work the ground, but streams came up from the earth and watered the whole surface of the ground — the Lord God formed the man from the dust of the ground and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life, and the man became a living being.

Without being slaves to ‘hallowed associations’ the team were aware of the resonances of much of the phrasing of Tyndale/AV and avoided making changed simply for the sake of novelty. Many passages, therefore, have a ‘familiar’ ring to them. Take, for example, John 14.1ff

‘ Do not let your hearts be troubled. Trust in God, trust also in me. In my Father's house are many rooms; if it were not so, I would have told you. I am going there to prepare a place for you. And if I go and prepare a place for you, I will come back and take you to be with me that you also may be where I am. You know the way to the place where I am going.’

Thomas said to him, ‘Lord, we don't know where you are going, so how can we know the way?’, Jesus answered, ‘I am the way and the truth and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me. If you really knew me, you would know my Father as well. From now on, you do know him and have seen him.’

In The Story of the NIV[6] Professor Calvin Linton explains the translators' approach to the rendering into English of Hebrew poetry. They adopted what he called ‘accentual scansion’ which is based on relying on the natural accent and stress of an emotionally charged syllable, with a differing number of accents in between, much in the manner of modern free verse. Here is the NIV version of Jonah's prayer:

“In my distress I called to the Lord,

and he answered me.

From the depths of the grave I called for help,

and you listened to my cry.

You hurled me into the deep,

into the very heart of the seas,

and the currents swirled about me;

all your waves and breakers

swept over me.

I said, ‘I have been banished from your sight;

yet I will look again towards your holy temple.’

The engulfing waters threatened me,

the deep surrounded me;

seaweed was wrapped around my head.

To the roots of the mountains I sank down;

the earth beneath barred me in for ever.

But you brought my life up from the pit.

O Lord my God

‘When my life was ebbing away,

I remembered you, Lord,

and my prayer rose to you,

to your holy temple.

‘Those who cling to worthless idols

forfeit the grace that could be theirs.

But I, with a song of thanksgiving,

will sacrifice to you.

What I have vowed I will make good.

Salvation comes from the Lord.”

And the Lord commanded the fish,

and it vomited Jonah onto dry land.

One of the passages which has been cited for comparative purposes in this series is the opening of Hebrews, which has been tackled with varying degrees of success. Cecil Hargreaves writes: ‘This passage is the beginning of one of the great traditional readings for Christmas Day and the Festival of the nativity. Some scholars think that vv.3 and 4 contain an early liturgical hymn, or strong traces of it. The whole passage is one long sentence in Greek, with many subsidiary clauses, a structure reproduced precisely by the AV. This makes the passage in the AV hard to read well aloud, which is a pity for one of the great classic pieces of AV wording.’[7] (Tyndale divided the passage into two sentences—see volume 2 of the Journal—whilst NIV uses three sentences.)

In the past God spoke to our forefathers through the prophets at many times and in various ways, but in these last days he has spoken to us by his Son, whom he appointed heir of all things, and through whom he made the NIVerse. The Son is the radiance of God's glory and the exact representation of his being, sustaining all things by his powerful word. After he had provided purification for sins, he sat down at the right hand of the Majesty in heaven. So he became as much superior to the angels as the name he has inherited is superior to theirs.

Whilst JB and NJB layout the opening verses of John's Gospel as poetry, NIV reads as prose:

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was with God in the beginning. Through him all things were made; without him nothing was made that has been made. In him was life, and that life was the light of men. The light shines in the darkness, but the darkness has not understood it.

(footnote offers the alternative ‘overcome it’).

Romans 8.18ff does not read so fluently as the JB version I quoted in the last article:

I consider that our present sufferings are not worth comparing with the glory that will be revealed in us. The creation waits in eager expectation for the sons of God to be revealed. For the creation was subjected to frustration, not by its own choice, but by the will of the one who subjected it, in hope that the creation itself will be liberated from its bondage to decay and brought into the glorious freedom of the children of God.

The vexed question of inclusive language has finally been addressed by the NIV Committee and a gender-inclusive edition was issued last year. God remains ‘Father’ and Jesus ‘Son’, unlike some other inclusive versions. Satan and angels remain masculine, but Mark 8.34, for instance, reads: ‘Those who would come after me must deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me.’ whilst Luke 4.4 now states ‘People do not live on bread alone.’ The non-gender-inclusive version is still available. This October (1997) Hodder Headline will be publishing the New Light Bible. ‘A new translation in the NIV family, designed for those who want an easy-to-read Bible which is clear and understandable.’ This is in line with the modern policy of targeting certain reading-age groups which affects Bible translation and publishing as well as other literary genres.

The booklet issued by Hodder Headline suggests the hope that the NIV might replace the King James Version as the single version which will be acceptable, but whether this is possible, or even desirable, is a debatable point. An article in the Expository Times (1990) suggests:

‘Much as we might wish to possess a translation which has been “authorised” by all the churches, large tracts of which we could come to know by heart as we once did the Authorized Version, ...the different aims and methods of the various translations, and a greater awareness of the uncertainties surrounding the biblical text, mean that none should attain to that place. To make anyone of them the Bible is to possess a sectarian spirit.. We must place the translations side by side, neither abandoning the older translations nor limiting our reading to our own favourite version.’

I wonder what Tyndale would have thought.

© Hilary Day