And the LORDE spake unto Moses, and sayde: In the fyrst daye of the firste moneth shalt thou set up the habitacion of the Tabernacle of wytnesse, and shal put the Arke of wytnes therin, and hange the vayle before the Atke. And thou shalt bringe in the table and garnish it, and brynge in the candilsticke, and put the lampes theron. And the golde altare of incense shalt thou set before the Arke of wytnesse, and hange up the hanginge in the dore of the habitacion.

(The ii. boke of Moses, The XL. Chapter, in the Coverdale Bible of 1535, g v recto)

Introduction[1]: The Contact between Tyndale and

Coverdale

The Coverdale 1535 is regarded as the editio

princeps of the English Bible. In their Historical Catalogue

of the Printed Editions of Holy Scripture, Darlow and Moule

admit that Coverdale's work 'does not rank beside Tindale's', but

add 'that it was Coverdale's glory to produce the first printed

English Bible, and to leave to posterity a permanent memorial of

his genius in that most musical version of the Psalter which passed

into the Book of Common Prayer, and has endeared itself to

generations of Englishmen'[2] As a printed book, it was

able to spread on a large scale and contribute considerably to the

unification of English language and culture. Given the spectacular

growth of the English language area in later centuries it may, with

the possible exception of Luther's German translation (complete in

1534), be identified as the world's most influential complete Bible

translation since the Vulgate.

Although Tyndale was in Vilvoorde prison by the time it appeared, his hand is recognisable in a lot of Coverdale's pages. In the above quotation from the beginning of the Second Book of Moses, for instance, the difference with Tyndale's text is very slight (Tyndale has '... unto Moses saying' where Coverdale has '... unto Moses, and sayde'; 'apparel' for 'garnish'; and a couple of minor variations in the word order). Coverdale was indeed able to work under Tyndale's supervision. That he worked with Tyndale in Hamburg in 1529 seems to some extent questionable. In his Tyndale biography, Mozley goes to great lengths to prove that we can safely accept this as a fact. He bases his interpretation of the historical events on Foxe's 'shipwreck' story. In the second edition (1570) of his famous Book of Martyrs, Foxe narrates how Tyndale tried to take his translation of the Fifth Book of Moses from Antwerp to Hamburg, but was shipwrecked.

Thus having lost by that ship both money, copies and time, he came in another ship to Hamborough, where at his appointment Master Coverdale tarried for him and helped him in the translating the whole five books of Moses, from Easter [March 28] till December, in the house of a worshipful widow, Mistress Margaret van Emmerson, Anno 1529, a great sweating sickness being the same time in the town. So having dispatched his business at Hamborough, he returned afterward to Antwerp again. [3]

On the next page, Mozley begins to quote at length another story, this time from Halle' s Chronicle, which suggests that Tyndale was not in Hamburg at that time but in Antwerp. He would have been arranging there, at the clever suggestion of the London merchant Augustine Packington, the sale to Bishop Tunstall of a complete print run of his New Testament translation.[4] The latter story may be less replete with inner contradictions and embellishments than Mozley assumes, whereas the former, which situates both Tyndale and Coverdale in Hamburg in 1529, requires much more evidence than has been found so far. Dr Francine de Nave, Curator of the Plantin-Moretus Museum in Antwerp, has communicated to me her serious doubts about Mozley's repeated argument of Antwerp being more than once 'too hot a place to be comfortable'[5] for Tyndale. We therefore remain in uncertainty about Coverdale's possible cooperation with Tyndale in Germany. We know for certain, however, that both he and John Rogers (editor of the second complete English Bible in print, the so-called Matthew's Bible of 1537) were with Tyndale in Antwerp in 1534-35. Evidence is given in J.F. Mozley's book on Coverdale. Printers often used scholars for the proof-reading and general editing of their publications, and Coverdale was apparently employed by Merten de Keyser [6] In the same publication, Mozley describes the role of the Antwerp merchant Jacob van Meteren in the preparation of the first complete Bible in print. In a biographical sketch of Jacob's son Emanuel by Simeon Ruytinck, there is a reference to Jacob van Meteren's zeal 'in bearing the cost of the translating and printing of the English Bible at Antwerp.[7]

Curiously enough, today Antwerp no longer seems to be considered as the place of printing for Coverdale's text. As places of publication, one usually finds names of towns followed by a question mark. Darlow and Moule suggest 'Zurich?' (printer: Christopher Froschover). For shelf mark S.Seld.c.9, the OLIS catalogue of the Bodleian Library in Oxford mentions 'Imprint [Cologne?]', whereas for shelf marks C.132.h.46 and C.18.b.8, the OPAC catalogue of the British Library speculates on' [E. Cervicomus and J . Soter? Marburg?]'. Pollard and Redgrave's Short Title Catalogue mentions the same printers as the OPAC catalogue, but associates their names with a different place: '[Cologne? E. Cervicornus a. .I: Soter?]'[8] Herbert's revised and expanded edition of Darlow and Moule keeps both options open: 'Cologne or Marburg'.[9]

L.A. Sheppard's Identification of the Place of

Printing

The confusion seems to be a result of the extent to which one

accepts the suggestions made in an article prepared by L.A.

Sheppard in 1935 (i.e. 400 years after the publication of the

Coverdale Bible). First of all, Sheppard demonstrates why Zurich

has to be rejected. All the recent catalogues follow him in this.

He then proceeds to an examination of initials, and finds that

'with a few exceptions the initials used in the Coverdale Bible

range themselves in two alphabets'.[10] He comes to the

conclusion that a 'peculiar distribution of the initials within the

volume lends support to the theory that the work was printed on the

presses of two printers [11] These printers are

Cervicomus (Hirzhom) and Soter (Heil). Having dealt with the close

connections between these two publishers, Sheppard finally reaches

the conclusion that in the course of 1535, Cervicomus must have

taken a unique blend of at least two sets of initials from Cologne

to Marburg, where he established a press in what was the seat of

the recently founded Protestant university, at which he

matriculated on 25 November of the same year.

Not all the initials fit within this theory. The explanation is also rather uneconomical, requiring considerable movement of initials, letter types and printers (admittedly phenomena not in themselves impossible at a time when types, initials and woodcuts were often handed on from one printer to another). Moreover, the colophon of the fIrst Coverdale mentions that the work was 'Prynted in the yeare of our Lorde M.D.XXXV and fynished the fourth daye of October'. This is before Cervicomus matriculated at Marburg university. Mozley sees this as an objection to Sheppard's argument. He accepts the latter's argument as long as it points to Cologne, but rejects the Marburg theory as 'an aberration'. [12] Mozley himself has to admit, however, that 'two odd capitals, one in Genesis and the other in Lamentations ...have not yet been found in Cologne books of this period'.

But one may wonder whether Simeon Ruytinck may be right after all when he indicates that van Meteren had the Coverdale Bible both translatedand printed in Antwerp. As I shall now go on to suggest, new evidence is perhaps to be found in one of its illustrations, and will have to be backed up by a renewed effort to identify its initials, types and historical setting.

The Postilla Print of the Tabernacle

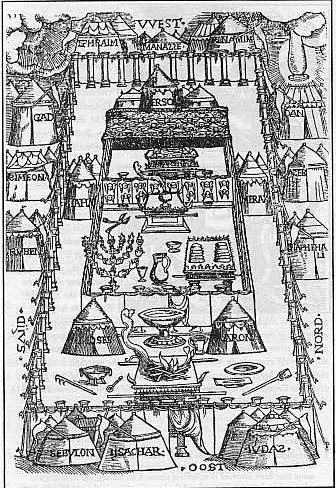

In the original, the quotation from Coverdale at the top of this

article (2nd Book of Moses called Exodus, ch. 40, 1-5) belongs to a

narrow strip of text

to the right of one of its larger illustrations (size 187 x 130

mm.) representing the Tabernacle, a copy of which is to be found at

the end of this article[13] It indicates the four points

of the compass in a language that is not English: 'west', 'nord',

'oost' and 'suiid'. In a characteristic error occurring when

woodcuts are copied onto a new block, the lettering in 'suiid'

(South) is partly upside down. A similar mirror effect is found in

the inverted 'S'-es in the names of SIMEON, MANASSE and IUDAS

(Judah) -- three of the twelve names of the Sons of Jacob, each

representing a tribe with its own tent. In the heart of the

picture, we see among others the ark and the veil, the

'candilsticke' with its seven arms, the table with the show-bread,

and the altar of the burnt-offering with the utensils. The same

illustration is repeated in the 4th Book of Moses called Numbers,

ch. 2, beside a narrow strip of text now identified as verse 9-13;

Coverdale 1535 mentions here that 'all they which belonge to the

hoost of Juda ...shall go before', and that 'On the South side

shall lye the pavylions and baner of Ruben with their hoost'.

There is nothing remarkable about the occurrence of words that are not English and not even Latin in a Woodcut of this vernacular Bible. The later Geneva Bibles in English frequently have French Woodcuts for the illustration of the Tabernacle. In the 1530s English was, after all, a language spoken by a population hardly larger than that of the Dutch and much smaller than that of the French language area in Europe. For the identification of the foreign language in the Coverdale Woodcut of the Tabernacle, the dictionaries WNT (Woordenboek der Nederlandsche Taal) and Grimm, relevant for the older stages of resp. Dutch and German, do not necessarily bring a solution (the spelling SUID, for instance, occurs in neither). Expert advice has therefore been taken from Prof. Dr. Jan Goossens, emeritus professor of linguistics at Leuven (Dutch-speaking Louvain in Belgium) and Münster (Germany), and from Prof. Dr. Joop van der Horst (currently professor of Dutch historiCal linguistics at K.U.Leuven). Both agree that the spellings SVIID (with double 'i' in capital letters) and IJSACHAR (with 'ij' instead of 'i' only) could occur in the whole of what is now the Dutch language area. The Dutch language developed out of 'Niederfrankisch' (Low Franconian). In Coverdale's time, however, these spellings could alSO have occurred in 'Ripuarisches Deutsch' (Ripuarian German), situated in the Aachen-Cologne area (i.e. close to but outside the Low Franconian area). In other words, they need not exclude Cologne as a place of origin of the Woodcut. The spelling NORD even includes the whole of both the Dutch and the German language area. However, the spelling OOST, with its characteristically 'Dutch' addition of a second 'o' as a lengthening mark, seems more definitely 'Dutch' (I rely on the experience of esp. Prof. Goossens here). It is therefore safe to say that the only language area in which the above-mentioned spellings for south, east and Issachar could occur, is Dutch.

It seems appropriate, therefore, to make use of Bart Rosier's invaluable study of The Bible in Print: Netherlandish Bible Illustration in the Sixteenth Century (1997) in order to identify the nature and possible origin of this woodcut. I have not found an identical copy in Rosier's publication, but the author reproduces only a fraction, impressive enough in itself, of the enormous amount of material he is dealing with. He does prove, however, that 'approximately eighty percent of the Netherlandish bibles were printed in Antwerp, and even if bibles were printed elsewhere, the illustration material came from Antwerp'[14] Since we know that Coverdale was definitely working in Antwerp, the eighty percent chance that the Dutch woodcut originates from Antwerp becomes even considerably larger.

B.A. Rosier also gives us solid background to our interpretation of the genre of the illustration. When we compare it with other illustrations in Low Countries Bibles, it becomes obvious that Coverdale's Tabernacle is atypical example of a so-called Postilla-print:

In almost all illustrated sixteenth-century Netherlandish Bible editions, prints appear that are based on the representations in the printed versions of the Postilla by the French theologian Nicholas of Lyra (ca. 1270-1349). The Postilla is a very comprehensive and in-depth Bible commentary that had been distributed over Europe in numerous manuscripts from the second quarter of the fourteenth century onward. ...The first printed edition of the Postilla illustrated with woodcuts appeared in 1481 by Anton Koberger at Nuremberg. This edition contained some forty prints.

Rosier adds on the same page that 'in general, Netherlandish Bibles feature the illustrations of the Tabernacle and the Temple, both with their accessories, placed to Exodus and 1 Kings'.[15] He also reminds us that 'incidentally, the illustrations accompanying the description of the Tabernacle in Exodus and Solomon's Temple in 1 Kings are the only woodcuts for which Luther used already existing prints as an example: the prints illustrating the Postilla by Nicholas of Lyra'.[16] The Luther who borrowed precious stones from aristocratic houses in order to have a direct experience of what Old Testament ornaments looked like, was obviously very critical about mediaeval illustrations, but the Postilla-illustrations are apparently reliable enough according to his judgment.

Further comparative study of illustrations of the Tabernacle in German and Low Countries Bibles is certainly needed to define more exactly the origin of Coverdale's illustration. At this stage, however, there seems to be little doubt that Coverdale's Tabernacle, if not his Bible, is of Low Countries rather than German origin, and that Antwerp is far more likely to have produced the illustration than any other typographical centre in the Low Countries.

Other Illustrations in Coverdale 1535

Thanks to the precious help and advice of Ms Nina Evans, Readers'

Adviser at the British Library , it has been possible for me to do

some preliminary investigation of the other woodcuts in Coverdale.

Darlow and Moule indicate that' altogether 68 separate woodblocks

are used, and by repetition these are made to form 158 distinct

illustrations'. Most of them are 'small cuts (generally about 70 x

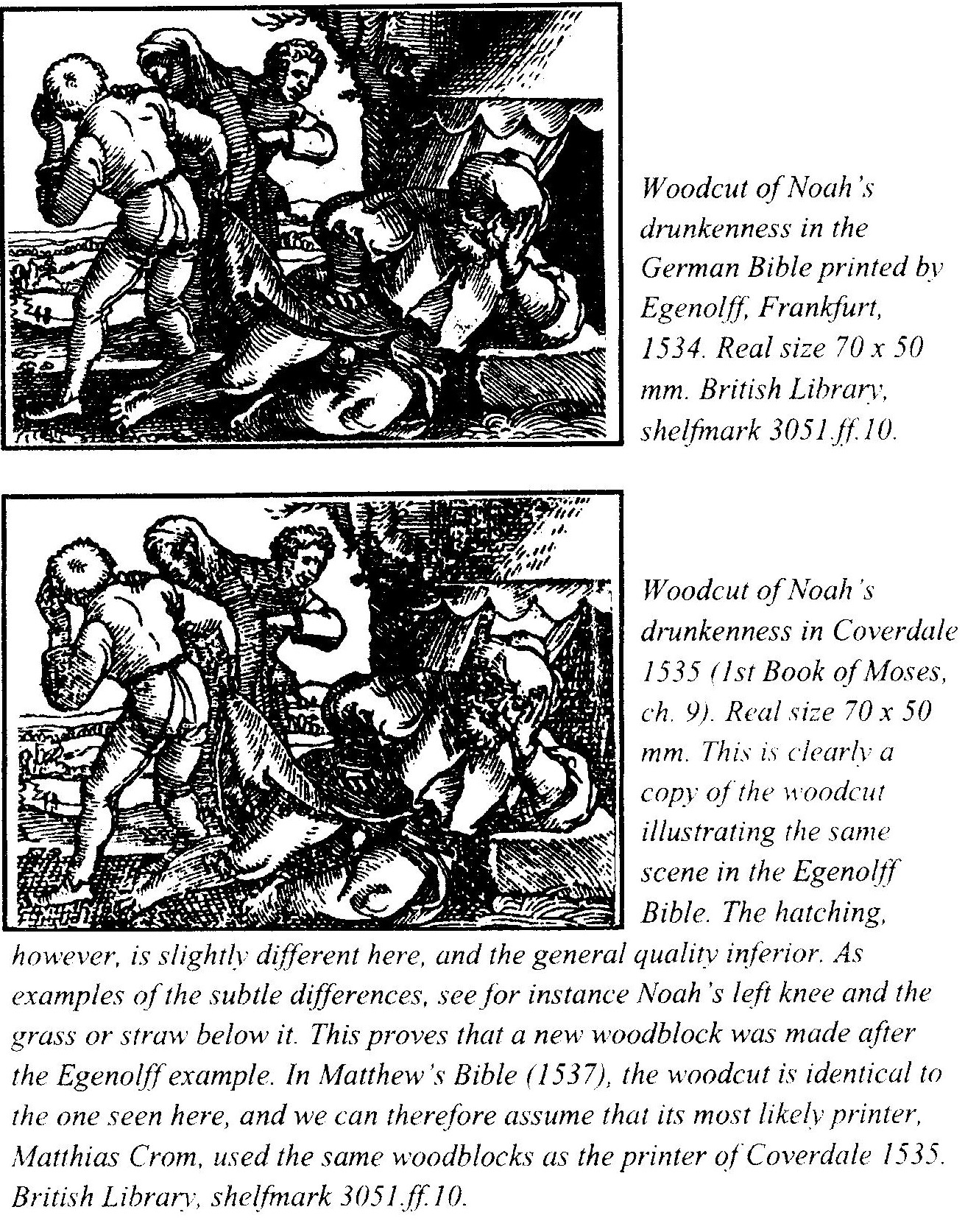

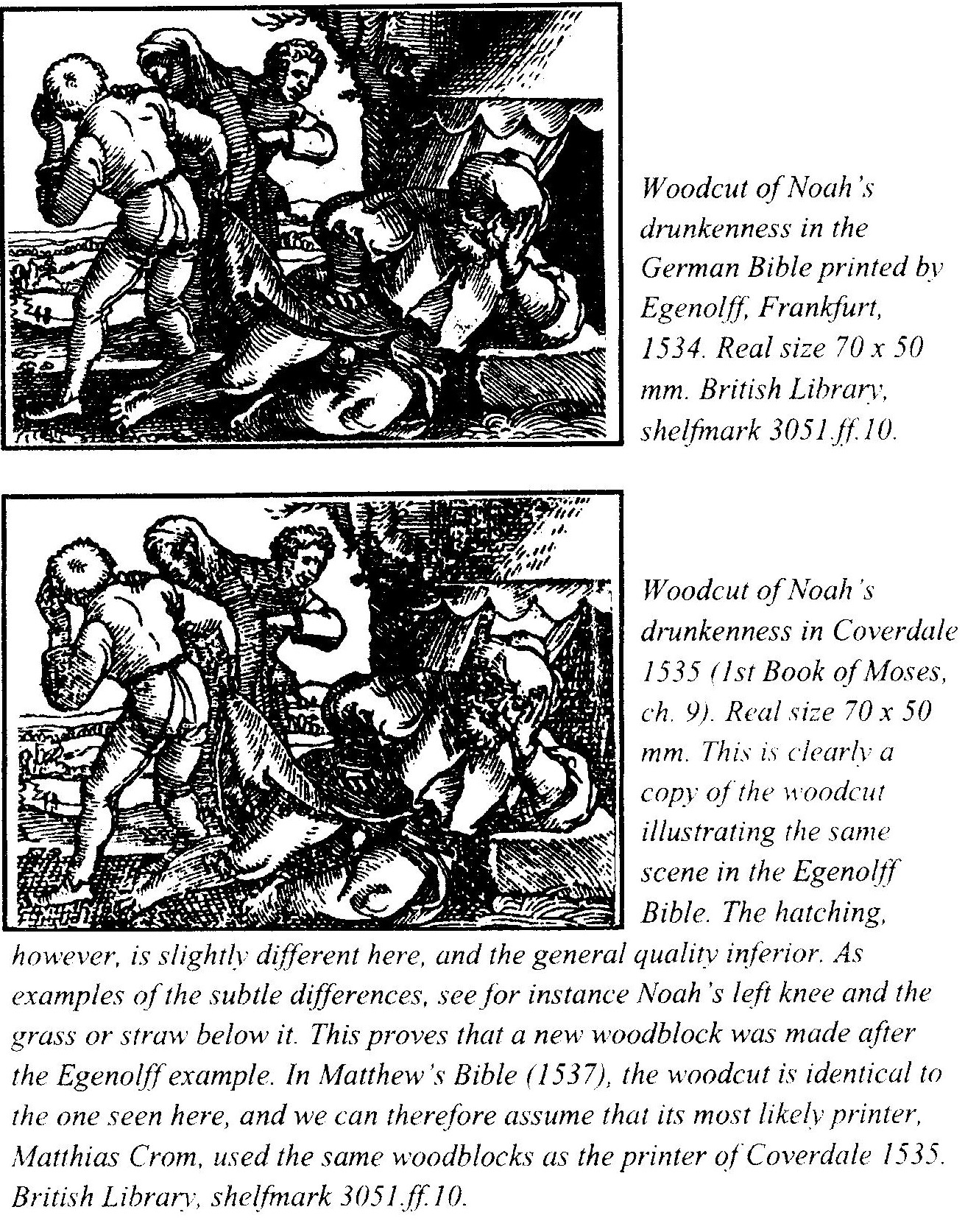

50 mm.)' [17] Two of these, viz. Noah's ark and Noah's

drunkenness (see illustration at the end of this article) are of

special interest to us, because they occur in

'a fragment, consisting of sig. a iii & iiij of pt. 1 only. With these leaves are bound the corresponding leaves from a copy of the German Bible printed by Egenolff at Frankfort in 1534 with types of the same class and containing woodcuts believed to be the originals from which those of Coverdale' s Bible were copied.'[18]

It would not be unusual for inferior copies of German illustrations to be made in the Low Countries. Especially before the days of Plantin, the French bookbinder who arrived in Antwerp in 1550 and became Europe's leading master printer there, the Low Countries printers owed much to the German ones for both their types and illustrations. German craftsmanship before 1550, with figures like Holbein the Elder, Holbein the Younger and Cranach, is generally recognised to be vastly superior to that of the Low Countries before the Plantin-Moretus dynasty of printers. It is significant that Coverdale' s small woodcuts of Noah's ark and drunkenness respectively are indeed copies of but not identical to their German models. In his entry on Coverdale in the Dictionary of National Biography (1887), H.R. Tedder remarked that Coverdale's 70 x 50 mm. woodcuts 'are the same design, with minute differences in the engraving'. Sheppard likewise mentions in 1935 that 'the illustrations of the Coverdale Bible are considered to be copies of Hans Beham's woodcuts in the Frankfort Bible'.[19] To the best of my knowledge, no one has ever contested this argument. Professor Meg Twycross (Lancaster University), a leading specialist on visual aspects of late mediaeval and renaissance literature, has looked with me at both sets of illustrations and agrees that the small woodcuts in the Egenolff original have a hatching slightly different from and a quality superior to Coverdale's. An example of the difference between Egenolff 1534 and Coverdale 1535 is to example of the difference between Egenolff 1534 and Coverdale 1535 is to be found in a comparison between their respective illustrations of Noah's drunkenness at the end of this article.

That most Low Countries woodcuts of those days were inferior to their German models, is of course no definite proof in itself that the small woodcuts in Coverdale are indeed from the Low Countries. In theory, slightly inferior copies could have been produced in Germany as well. It would be a mistake, however, to assume that copies of Hans Behamuse the latter's woodblocks. All we can claim so far for the smaller illustrations in Coverdale is that, as was apparently the case for the Postilla-print with its miscalculated mirror effects, an in some respects somewhat clumsy reproduction was made by anew craftsman who may well have worked outside Frankfurt or Cologne and even outside Germany.

Identical Small Woodcuts in Matthew's Bible

According to Darlow and Moule, Matthew's Bible 'welds together the

best work of Tindale and Coverdale', and 'is generally considered

to be the real primary version of our English Bible',

[20] -- as distinct from the Coverdale 1535, which is

the editio princeps. It was published with King

Henry's licence. In his recent Tyndale biography, David Daniell

places it with certainty in Antwerp[2l Herbert follows

Darlow and Moule when he writes that 'conjecture points to

Antwerp'[22] The always very circumspect Nijhoff and

Kronenberg hesitate only very slightly: 'Het komt

ons bijna zeker voor, dat Crom de drukker is'[23]

(it seems almost certain to us that [Matthias] Crom [from Antwerp]

is the printer), and add substantial evidence based on woodcuts and

initials.

Six illustrations in Matthew's seem to me to be not simply copies, but exact matches of Coverdale woodcuts. Here is a comparative list of them:

| Coverdale 1535 | Matthew 1537 | Representing |

|---|---|---|

| a1r | a1r | 1st page Genesis |

| a2r | a1v | Adam & Eve and the Tree of Knowledge |

| a2v | a2r | Cain slays Abel |

| a3v | a3r | Noah's ark |

| a4v | a4r | Noah's drunkenness |

| b3r | a8r | Abraham's sacrifice of Isaac |

A magnifying glass might reveal that in these six cases, the same woodblocks were used again. By the time they are used for Matthew's, the only difference seems to be that they are two years older, as is revealed in tiny imperfections found in Matthew's and not in Coverdale. It would be useful for a more expert eye to look at this.

If we can safely assume that the blocks were the same and that Matthew's was printed in Antwerp, it also becomes extremely likely that not only the larger but also the smaller illustrations in Coverdale were of Antwerp origin. Woodblocks of course do travel from time to time, but it is an uneconomical assumption that the blocks large and small would have been made in the Low Countries, then taken to Germany for the printing of the Coverdale Bible, after which the smaller blocks were carried back to Antwerp for the printing of Matthew's. It is much more likely that they were all made in the Antwerp area and simply remained there for the printing of both complete Bibles.

Types and Initials

All sources agree that the printer of Coverdale 1535 used a

Schwabacher -a type general enough not to tie it to a particular

place in Pennant or the Low Countries. The story of the initials

will have to be reconsidered in the light of the new evidence

regarding the illustrations. Sheppard's article has so far remained

the most authoritative source on this issue, whether it is followed

to its utmost conclusions (leading to Marburg, as the British

Library catalogue assumes), or whether it is accepted only

partially (identifying Cologne as the place of printing, as the

Bodleian Library following Mozley suggests). A valuable source of

information not at Sheppard's disposal in 1935 is Vervliet's 1968

publication on printing types in the Low Countries[24] A

search involving Vervliet's reference work will have to be carried

out. It will have to be systematic, and if possible include some of

the latest techniques involving computer scanning in contrasting

colours. Prof. Pam King (University College of St Martin,

Lancaster) has suggested making use of the facilities offered at

her university by the Imaging Science Department, which has

experimented with this technique on mediaeval manuscripts -with

good results. This kind of scanning can be applied to both types,

initials and illustration.

That one or more woodcuts in it are of Low Countries, presumably Antwerp origin, does not automatically lead to the conclusion that the entire Bible was made in Antwerp. Again, it is types and initials that will have to provide more conclusive evidence. Scholarly works on Dutch Bibles in print, such as Rosier's above-mentioned study, or Den Hollander's meticulous work on Dutch Translations of the Bible 1522-45,[25] will have to be consulted. My colleagues expert at rare books of the 16th century at both Leuven (Dr Chris Coppens) and Louvain-la-Neuve (Prof. Jean-Francois Gilmont) have urged me to consult Valkema Blouw, a great authority in the field of 16th century printers. There is, in other words, a great deal of work still to be done on types, initials and illustrations.

Some Further Historical Paths to Explore

A reconsideration, in a more historical context, of the van Meteren

connection should likewise be very useful. Mozley assesses the

climate in Antwerp in 1535 as follows:

How did things stand in the summer of 1535? At Antwerp the reformers were in trouble. Tyndale was arrested in May, and his English friends found themselves in peril; a general hunt was made for Lutherans and their books, and Meteren's own house was searched. That Meteren should determine to print elsewhere is easy to understand; and if elsewhere, where better than at Cologne, which was within easy reach, and where archbishop Hermann of Wied held the reins of power. Hermann was more than half a Lutheran, and in due course initiated those reforms, which brought down on his head the wrath of the papacy and led to his excommunication a few years later. Cologne had never lacked printers of liberal and humanist outlook, and among these are particularly named Quentel, Soter and Cervicom.[26]

Mozley's determination to see things through the eyes of Tyndale may perhaps make him slightly myopic here. Antwerp, like Cologne, was printing masses of materials of humanist and protestant outlook. One can mention, for example, an edition of Jacob van Liesvelt Bible in the very year 1535. In 1526, van Liesvelt brought out the first complete Dutch Bible translation in print, which he based on Luther inasmuch as he could (Luther's own Bible translation not being complete yet). Its 1535 edition has a woodcut showing Jesus being tempted by the devil in the desert; the latter appears in the shape of a monk complete with horns and cleft feet. Nevertheless, printers like Liesvelt and Vorsterman did not refrain from printing fervently anti-protestant materials either. The guiding principle seems to have been commercial profit here, and this applies to both printers and city magistrates. The Antwerp community simply could not afford to antagonize its most significant group of foreign traders, i.e. the English, and even Bible translation, harsh though it may sound to those who gave their lives for the spiritual welfare of the faithful, was business as usual. It is precisely the relative protection this commercial attitude gave to Englishmen that explains the complex issue of Tyndale's arrest. Tyndale would have been extremely well protected within the walls of the English house, enjoyed less safety within the city walls of Antwerp, and would have lost even this relative safety in the fields outside these walls, where he met King Henry's emissary Stephan Vaughan.[27] At any rate, Mozley's argument about reformers being 'in trouble' at Antwerp, although not entirely wrong, is not sufficient to make us assume that van Meteren must have had the complete Bible translation in English printed elsewhere. Most importantly, it does not take into account the huge number of Protestant Bibles. Most of these were printed in Dutch and therefore at far greater risk in the same town than any English Bible would be.

These various lines of research will, it is hoped, yield conclusions worthy of publication by Dr Kimberly L. Van Kampen, Curator of the Van Kampen Collection. She was the exemplary hostess of the Hereford symposium (28- 31 May 1997) on The Bible as Book, where she generously offered the author a place for publication of a more definitive version of this text. It should appear in a collection of papers that will be submitted for consideration as the third volume in the Scriptorium's series with the British Library. The text to be submitted soon to Dr Van Kampen will, it is hoped, contain new arguments in favour of Antwerp, while at the same time being sufficiently armed against this hope. Considering the evidence available at the current stage, however, Antwerp can already be named as the most likely place of origin for the Coverdale Bible of 1535. When confIrmed, this hypothesis would very much consolidate the historical link between on the one hand the pupils Miles Coverdale and John Rogers, and on the other the great master William Tyndale himself. Above all, it would enhance the connection between Antwerp and the genesis of the English Bible as we know it today.

Guido Latré

K. U. Leuven and Université Catholique de

Louvain

The author welcomes suggestions, advice and criticism at the following address:

Dr Guido Latre

Arts Faculty K.U.Leuven

P.O.Box 33

B-3000 Leuven

Belgium

Tel. +32-16-324881, fax +32-16-325068

E-mail: guido.latré at arts.kuleuven.ac.be

|

|

Postilla-print of the Tabernacle, Coverdale 1535, 2nd Book of Moses, ch. 40 (real size 187 × 130 mm.) |

|

|

|

|

References