Geneva Tyndale Conference 2001 — Papers and Reports

Introductory Remarks

On behalf of the organising committee and myself I should like to warmly welcome you all both delegates and speakers to this second Geneva Tyndale Conference. We know that some of you have come a considerable distance to be here with us and we are confident that you will find the journey worthwhile. We have delegates and speakers from America, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Germany, Britain many parts of Switzerland. No doubt I have omitted a country. Please do not contact your ambassador to make an official complaint, just have a quiet word with me afterwards so that I can carry out the appropriate penance!

I doubt whether any of you are aware that by complete coincidence although I would like to claim credit for it, I have to admit this, as even conference organisers cannot think of everything in advance — that this weekend is a very special one in the history of Geneva and the Reformation in general. It was here in Geneva that Michel Servet, the 'Hunted Heretic' in the historian's Roland Bainton words[1], during his lifetime the thorn in the side of Calvin and thereafter on the Reformer's stricken conscience for eternity, was tried for heresy on the 26 October 1553. Calvin wrote to Farel on that date:

he (Michel Servet) was condemned without dissent. Tomorrow he will be led to execution.

The sentence dated the 27 October was carried out the same day at Champel then just outside the Geneva's city walls, where a monument now stands, erected in 1902 at the instigation of Emile Doumergue, to expiate the collective conscience of the city. The inscription reads:

We are respectful and grateful sons of Calvin, our great Reformer, but we condemn an error which was that of his century and we are strongly attached to freedom of conscience.

It is interesting to note that he was finally condemned on only two counts: anti-Trinitarianism and anti-paedobaptism. The verdict of the 27th October read:

The sentence pronounced against Michel Servet de Villeneuve of the Kingdom of Aragon in Spain who some 24 years ago printed a book at Hagenau in Germany against the Holy Trinity containing many great blasphemies ... in the teeth of the remonstrances made to him by the learned and evangelical doctors of Germany ...

He confesses that because of this abominable took he was made prisoner at Vienne and perfidiously escaped. He has been burned there in effigy together with five bales of his books. Nevertheless, having been in prisoner in our city (i.e. Geneva), he persists maliciously in his detestable errors ..

Wherefore we Syndics, judges of criminal cases in this city, having witnessed the trial conducted before us ... condemn you Michel Servetus, to be bound and taken to Champel and there attached to a stake and burned with your book to ashes.

So it is appropriate that we, on the 27th of October 2001, should be attending, in the very city Geneva where Servet suffered so cruelly for his heresy, a Conference entitled Books for Burning. We all know the story of the buying up and burning of Tyndale's Bible by Bishop Tunstall in 1526. The Tyndale Window in the Bristol Baptist College shows Cuthbert Tunstall standing sternly in his pulpit outside St Paul's Cathedral overseeing the burning of copies of Tyndale's translation of the New Testament and a monk hurrying forward carrying so many books in his arms that he has to steady the pile with his chin[2], But this was no isolated incident. In 1538 an attempt was made to print a revision of the so-called Matthewe's Bible in Pans where the paper was both better and cheaper than in England (this will strike a chord with our Danish speakers). Notwithstanding a royal licence obtained from Francis I, the king of France, the print run of 2500 copies was seized and condemned to the flames.

So closely linked were the heretical writing and the heretic that there were cases of a deceased offender being disinterred and burnt with his book — a fate suffered by Martin Bucer, who had been elected Professor of Divinity at Cambridge in 1550. Incidentally, a scholar dryly remarked that the warmth of this welcome seems to have frightened scholars off Cambridge for many a year! A century earlier Wycliffe's books were burnt in Prague after a decision by the Council of Constance — and we could possibly hear about the trials and tribulations of Wycliffe in Dr Steve Sohmer's presentation this afternoon. Prof Thiede would be able to counter this with the burning of Martin Luther's German Bible in 1624 or even, a century earlier, when Luther's books were burnt in Cambridge in 1520 and also on 12 May 1521 near St Paul's Cathedral in London. Sir Christopher Trychay, the priest of Morebath in Devon, who gives an excellent, albeit unwitting, account of the path and effect of the Reformation in England on his remote Devon parish in his meticulous churchwarden's accounts compiled during the 16th century, almost certainly lost his church's copy of the Book of Common Prayer, purchased for 4s 4d, in the general burning of books in the Prayer Book rebellion of 1549[3].

Not that this burning of books was confined to Europe. In 1650 the Puritan authorities confiscated and put to the torch William Pychon's The Meritorious Price of Our Redemption on October 20 in Boston marketplace. This may have been the first book burning in America: among the latest, was that in 1990 on October 23 — October is clearly the 'in' month for this sort of activity — when the entire print run of Fortunate Son was burned on the insistence of the Bush family — no comment.

But enough of this catalogue of outrages against books for as Camille Desmoulins replied to Robespierre who burnt his newspaper the Vieux Cordelier on January 7 1794 for criticizing his reign of terror, 'Burning is no answer'. What was happening to cause this in the Reformers' case? Well, one very influential factor was the progress of vernacular translations of the Bible. First they were manuscripts (small piles) and, then much more significantly, printed versions (large piles and unending as they could be run off so quickly). And that is what we are going to hear about and discuss today — we shall be informed on the fate of a vernacular manuscript Bible, Wycliffe's, by Dr Steve Sohmer, on printing in Antwerp through the expert guidance of Dr Guido Latré; we shall be given a general view by Prof Carsten Thiede of the progress of vernacular Bibles from Tyndale and Luther to the present day with the magnifying glass, as it were, focussed on St John's Gospel. We shall then make an exciting geographical diversion led by Peter Raes and Paul Rosendahl to discover what happened in Denmark and Iceland and finally Prof David Daniell will rock us all back to Geneva with his intriguing theory on the 1560 Geneva Bible — a very much underrated English vernacular Bible.

I must confess that I am hoping that he will comment authoritatively on a theory which, as a Geneva resident, I have long held dear. Could it be that most of the input can be traced to a copy of the Tyndale Bible brought to Geneva by an exile, to the presence of Miles Coverdale and to that of a further group of exiles: William Whittingham, Thomas Sampson, Christopher Goodman, William Kethe, William Cole, John Baron, John Knox, Thomas Lever, Anthony Gilby, Lawrence Humphrey?[4]

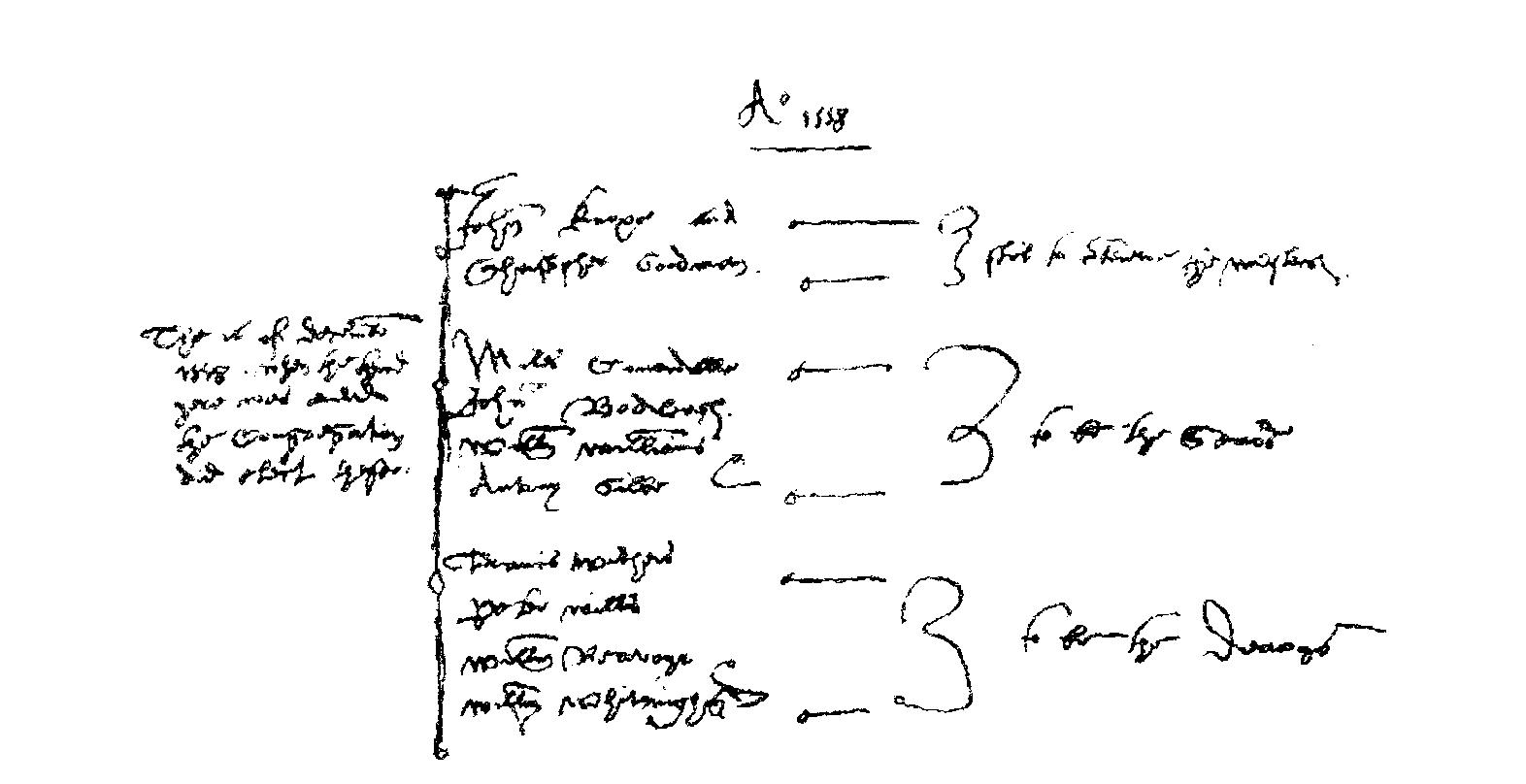

Livre des Anglois entry for 1558

| John Knoxe and Christopher Goodman |

stil to continue the ministers | ||||

| The 16 of decembr 1558: when the third yere was ended the Congregation did elect these. | Miles Coverdalle John Bodleigh Willm Williams Antony Gilbe |

to be the seniors | |||

| Francis Withers Peter Willis Willm Beavoyr Willm Whitingham |

to be the deacons | ||||

Transcription of Livre des Anglois entry for 1558

The output of Geneva was incredible in such a breathtakingly short period of time producing as it did vernacular versions of the Bible, the Prayer Book and a Psalter in some five years (1555-1559) — the work of a small but definitely A+ team (in modern football parlance the equivalent of a Manchester United). This group included very influential, intellectual clerics who went on to hold high office under Elizabeth, rich merchants like John Bodley and rich noblemen like Sir William Stafford, and they were able them to print their work quickly due to the presence of Rowland Hall.. And, as we all know, no one will usually re-invent the wheel — the existing Bible translations were in their possession and we may rest assured that they used them. The team worked hard refining, translating, innovating, editing, enlarging and improving. But we wait for David to reveal all in the final lecture of the Conference. Be warned, and do not overindulge at lunch or you may miss out on The 1560 Geneva Bible; The Shocking Truth.

It is now my pleasure to invite Prof. David Daniell, world expert on William Tyndale and one of the leading experts in the world on the English Bible, to welcome you, in his capacity as Chairman of the Tyndale Society, to this the second Geneva Tyndale Conference.

© Valerie Offord, 25 October 2001.

References

| [1] | Bainton, Roland H. Hunted Heretic: The life and Death of Michael Servetus 1511-1553, Beacon Press, Boston 1953. |

| [2] | Osborn, Peggy The Tyndale Window, Bristol Baptist College Tyndale Society Journal No.19, August 2001. |

| [3] | Duffy, Eamon The Voices of Morebath: Reformation and Rebellion in an English Village, Yale University Press, 2001. |

| [4] | Livre des Anglois or the Register of the English Church at Geneva under the Pastoral Care of Knox and Goodman 1555-1559. Authenticated printed copy of 1913 in Holy Trinity Church Archives, Geneva. |