![]()

Ploughboy Notes and News

Working Party

David Ireson the Ploughboy Group Convenor is keen to hear from teachers prepared to join a working party looking at educational materials for use in the UK and USA.

Please contact him for further information: David.Ireson@btinternet.com or tel: +44 (0) 1984 631228.

Notes from Tyndale Country

David Green

April 2003.

Living as I do in a small village on the watershed between Severn and Thames and close to the western scarp of the Cotswold hills, I can walk to the edge and look over the Severn valley and the vale of Gloucestershire to the tower of Gloucester Cathedral and beyond to the forest of Dean, the Malvern hills and the distant Welsh mountains.

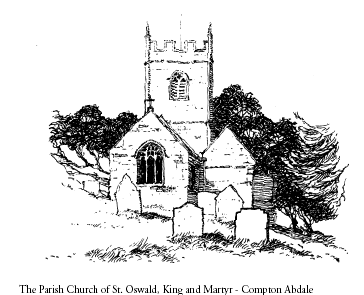

Much closer to home is the tiny village of Compton Abdale in another fold of these hills. This was prime sheep rearing country in the 1400s when the Bishop of Worcester and the Lord of Berkeley ran great flocks and the worth of Cotswold fleeces was well told in the cloth halls of Ghent, Ypres and Bruges.

The wolds are now an officially designated ‘Area of Outstanding Natural and Architectural Beauty’ and only a few hundred of that famous ‘lion’ breed of long wool sheep survive. The word wold signifies wooded upland and the whole area was forested in the Middle Ages. Most houses were timber framed until wood became scarcer due to deforestation and the hills became largely bare sheep runs. Later centuries saw both poor and rich using the local honey-coloured limestone for house building, and the wool towns and wealthy merchants’ houses now draw in tourists and ‘incomers’ like myself. In my spare time I work as a voluntary Cotswold Tree Warden and with other wardens from many parishes try to plant and care for as many new trees as possible.

In 1993 a local lady, Katja Kosmala, another ‘incomer’, wrote ‘Compton Abdale in the Cotswolds’, a finely researched and superbly produced large format paperback of which only one thousand copies were printed. I never met Katja - sadly she died several years ago. I also found that Longhouse, her publisher in Winchcombe, was no longer operating in the UK. However, I have traced her son Rupert, who now lives in America, and have his permission to reprint a chapter from her book. Therefore in Katja’s memory and on account of the coinciding interests of my adoptive landscape and Tyndale studies, I would like to quote in full her chapter 18 which describes the impact of the Reformation on a small Cotswold community.

Explanatory note on the chapter entitled ‘The Reformation’ from Katja Kosmala’s book

The Priory referred to at the outset is the Priory of St Oswald in Gloucester. Together with the nearby barony of Churchdown on a hill midway between the town and village, it was held under the spiritual jurisdiction of the Archbishop of York. At the dissolution both were transferred to King Henry and then to the new Bishopric of Gloucester in 1542. The tithes and glebelands were eventually ceded to the Dean and Chapter of the Cathedral of the Holy Trinity in Bristol.

The Reformation

being chapter 18 of Katja Kosmala’s book ‘Compton Abdale in the Cotswolds’

Though the connection between the manor of Compton and the Priory had been broken so long ago that it must have been forgotten, strong links remained between the parish and the canons until the Priory ceased to exist in 1536, for the Prior as Rector of the parish appointed the priest and also owned the glebe (Rectory Farm). True, the farm had been let for many, many years, but as we know, the Prior and Chapter had a room, a cellar and stables there. Remembering their fondness for country life, we can be sure that they made use of this pied-à-terre to the last.

John Rogers’ will of 1498[1] confirms the good relations between the village and the Canons, or at least between John Rogers and the Canons. He leaves 4d to each of them, 6s 8d to one particular Canon, Sir Philipp Herford; to the mother-church in Gloucester 20s, “which John Cassy owes me”, and 2s. to the three orders of friars, which is a tribute to their popularity as preachers. Canon Herford seems to have be a personal friend, for he witnesses the will and receives more than anybody else outside the family.

Then all this friendly intercourse suddenly came to an end. The Priory was dissolved, the canons dispersed. They would not come riding up from the vale any more and their room in the farmhouse -- and their cellar! - - would not be needed any longer. Rectory Farm had no more business in Gloucester and the traffic between village and town dwindled. St. Oswald’s no longer had a mother-church and the priest was on his own, though nominally the Archbishop of York had spiritual jurisdiction until the new bishopric of Gloucester was created in 1542.

The Dissolution of the Monasteries was, of course, not the first of the profound changes and upheavals which we now call the Reformation and which would continue for a century and more. The king’s divorce and the break with Rome had preceded the Dissolution, but how much these events which reverberated throughout Europe shook the small village in the Cotswolds, we have no means of knowing. The disappearance of the Priory would, we imagine, have affected Compton more than the royal Supremacy. But the king’s private life, which was not so very private after all, would certainly have been irresistible to comment on unless people in 1535 were very different from people in 1935, although in hushed voices -for it was dangerous to take sides or to express sympathy for the wronged queen. Whatever happened in those fateful days happened in London, and few country people would go there and have firsthand knowledge. Hearsay and rumour must have been the main vehicles by which news travelled into the villages. Then, in 1535, the king and Anne Boleyn came to Gloucestershire. They stayed in Fairford with John Tame and, passing through Cirencester, rode on to Prinknash. Was anybody in Compton curious enough to travel to Cirencester to get a glimpse of the woman who apparently had caused all the turmoil? Who was the reason that the king had put himself in the place of the Holy Father as Head of the Church in England?

But although the King defied the Pope, he did nothing to disturb the faith of his people. He had been given the title Defender of the Faith for his polemic against Martin Luther and he remained as averse to the radical Reformers as he had been before his break with Rome. His Six Articles upheld the tenets of Catholic religion and were enforced with severity. Churches, as well as the Service, kept their reassuring familiarity. Mass was said in Latin, as it always had been, and Confession and Absolution eased the sinners’ consciences. Joan Rogers [2] bequeathes “to ye hye alter a draper bord cloth to make alterclothes and also to ye sacrament a kercheve to be upon ye pyx”, and making her will in the 37th year of “our sovereign lorde king Henry ye 8th supreme head immediately under god of the church of England”, (1546) she bequeaths “my sowle to Almyghty God, to our Lady Saint Mary and to all the wholy company in Heven” with all the trust of her forebears.

When, however, the young king followed his father on the throne, the Reformers were given free rein, and Protector Somerset constantly asked Calvin, the most radical of them, for advice. Calvin, though, complained that the Reformation in England was not thorough and quick enough. It was, in fact, too fast for the people to assimilate and absorb. Already in Edward’s second year as king, Latin in the Service was abolished and the Liturgy had to be in English. Images, tapers, holy water and side altars were removed, the celibacy of the priests done away with, and many made use of the freedom to marry. The saints and - worst of all - the Virgin Mary were banished from Heaven. Belief in Purgatory was disapproved of and prayers for the dead forbidden. Confession was not prohibited outright, but gradually died out through discouragement.

All this went to the very heart of popular faith and religious life, and evasion and resistance were the natural response to such shattering deprivations. But King Edward in his turn was as severe as his father had been. Roman worship was prohibited and offenders were punished with prison for hearing Mass. The king would not even make an exception for Princess Mary, his half-sister, who had petitioned to have Roman Services privately in her residence. All these reforms could not be enforced everywhere at once. The diocese of Gloucester, however, was not allowed to ignore the new spirit for its bishop was one of the most ardent Reformers.

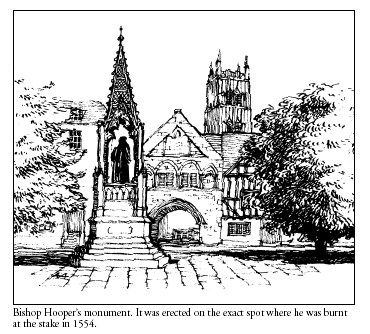

Bishop Hooper had early on come under the influence of the Continental Reformers, Zwingli and Bucer, and had had to leave England when the Six Articles came into force in about 1540. He stayed in Switzerland for some years and when he returned to his own country he was, more than ever, convinced of the rightness of the new teaching and more zealous for implementing it. His dedication was soon noticed and he was made Bishop of Gloucester in 1551. But his radical attitude nearly wrecked his episcopal career before it began because he chose to be imprisoned rather than consent to wear the traditional vestments at his consecration. A compromise was eventually reached, he was released from prison, consecrated, and went to Gloucester to redeem his province.

He found much to do. The backwardness of the diocese, the apathy and the conservatism of the higher clergy, the corruptness and ignorance of the parish priests might have discouraged any but the most dedicated and zealous reformer. Nevertheless, Bishop Hooper attacked these evils with untiring energy and devotion, “going about his towns and villages in teaching and preaching to the people there”, acting as judge in the diocesan court to defeat the cumbersome mediaeval procedure, “he left no pains untaken nor ways unsought how to train up the flock of Christ in the true word of salvation.” [3] This was always his ultimate aim, but to save the flock, he had to reform the shepherds first.

One of his first acts [4] was to examine the clergy in the fundamental and most important Christian subjects: the Ten Commandments, the Creed and the Lord’s Prayer, and only 79 out of 311 examined clergy were wholly satisfactory. Nine did not know how many commandments there were, 33 did not know where to find them, the gospel of St. Matthew being the favourite place to look for them; 168 could not recite them. Only 10 could not recite the Creed, but most of them, - 216 - could not prove it from Scripture; 39 could not find the Lord’s Prayer, 34 did not know its author and 10 could not recite it.

Judged against this background, Compton’s minister, Johannes Roodes, appears quite satisfactory [5]; he could answer all questions, bar one, the scriptural proof of the Creed, but 215 others failed in this point too.

Ignorance was not the only failing of the clergy which Hooper’s unceasing vigilance brought to light. The low standard of morals and behaviour is reflected in the cases before the Diocesan Court. Violence, incontinence and keeping a woman in the house, sortilege or sorcery, and forging a will - all these occur. The hawking and hunting for which the vicar of Toddington is taken to task may not become the “sober, modest, keeping hospitality, honest, religious, chaste” parson who was the bishop’s ideal, but it was one of the more innocent shortcomings.

A frequently recurring charge is “superstition”, that is Roman practice. While the royal Supremacy was fairly easily accepted - the vicar of South Cerney, among others, even thought that the Lord’s Prayer was so called because the Lord King had given it in his Book of Common Prayers - the spirit of the Edwardian reform penetrated the depth of the country but slowly. What had been believed and practised since time out of mind could not be eradicated overnight. The incumbents of Hazleton, Hampnett and Turkdean were found guilty of superstition, and the rector of Hawling was ordered to preach more often. Johannes Roodes, Compton’s priest, is not mentioned in any of the Court records. He apparently led a quiet and blameless life and conformed, at least enough to keep him out of court. Had he been a gross sinner, he certainly would not have escaped the bishop’s attention.

The bishop seems to have been satisfied with Compton Abdale [6], church, priest and parish alike, for it is mentioned but only once in the extensive records of his episcopate and then only in respect of the church yard wall. This was found in need of attention and Compton was given a fortnight to repair it. Strangely enough, four men are recorded to have objected to this request and stranger still, one of them was Johannes Roodes.

There is no record of the Protestantization of Compton church, but no admonition to carry it out either. The reform of the parish churches had begun in piecemeal fashion before Hooper came to Gloucestershire: under his zealous eye, however, it gathered momentum. Of all the changes the Reformation brought the spoilation of their church certainly was the hardest to accept for the village people. The church then was not aloof from the village, to be visited for Sunday Service and not again until the next Sunday, but part of everyday life; church, village hall and even market place, all in one, the churchyard was a playground and meeting place. The old table-tomb just asked to be used as a seat, and the young men did not hesitate to chip holes into the slab for playing Nine Men’s Morris. It was their church, familiar yet mysterious at Service time, when the priest celebrated Mass at the High Altar for which Joan Rogers had left the altar cloth only a few years before. There was the eternal lamp, which her kinsman, John Rogers, had provided by a bequest of 20 sheep to the church, there was the flicker of the candles on the side altars, given and lit in supplication to a saint or the Virgin or as thanks for help received. The paintings on the walls had been studied from childhood and Christ crucified, His Mother and St. John had looked down on them from the Rood Screen all their lives.

By royal command the church was stripped of all these sacred and familiar things. The rood-screen had to be dismantled, the lamp and the candles extinguished, the walls were whitewashed, the “idols” of the saints and Virgin Mary disappeared, the holy water stoop was removed – the church was bare and empty.

We can only try to imagine the pain and bewilderment of the people in Compton, and countless other parishes up and down the country, when they found themselves in this austere place of worship, deprived of the intercession of the “company in heaven” and the comfort of the Mother of Our Lord, venerated and dear, and nearer to the hearts and minds of the worshippers than the remote Godhead. Yet they had responded loyally, but when the bishop was still not satisfied and ordered the repair of the church yard wall, reasonable though the request appears, they protested. They protested against perhaps more than the churchyard wall.

Bishop Hooper worked unceasingly and never sparing himself, not only in one diocese but two, for he had to look after Worcester as well [7]. His wife worried because of his overworking and feared he might break down. He probably would have ruined his health, given time, but, after two and a half years of his episcopate, King Edward died and with the accession of Queen Mary the Reformation came to a halt. Hooper was ordered to London and deprived of his office because of his marriage and his denial of transubstantiation. After a stay in Fleetwood prison, where he was treated harshly, he was sent back to Gloucester. People lined the street and wept when he passed, though he had been such a severe task master. He was burned at the stake near the church of St. Mary Lode, half-way between St. Oswald’s and the Cathedral, where his monument stands now, on February the 9th, 1554. Bishop Hooper’s monument. It was erected on the exact spot where he was burnt at the stake in 1554.

His diocese settled back into Catholicism easily; there were no martyrs in Gloucestershire. His successor, Bishop Brooke, was a mild man, a state of apathy returned and Gloucestershire “enjoyed much quiet”. (Fuller)

Editor’s note

We are very grateful to Rupert Kosmala, for allowing us to reproduce this chapter from

his mother’s book. It was a limited illustrated edition of 1000 copies published by

Longhouse of Winchcombe in 1993 and is now out of print.

Notes and references

| [1] | Hockaday Abstracts |

| [2] | Will no. 93 Gloucester Diocesan Register |

| [3] | Clarke, Dr A. Foxe’s Book of Martyrs Ward Lock & Co London p.21 |

| [4] | Gloucester Diocese under Bishop Hooper Brit. & Glos Archaeological Soc Trans Vol. 60 1938 |

| [5] | vol 6, 124 Gloucester Diocesan Register |

| [6] | Bishop Hooper’s Act Books |

| [7] | ‘…I entreat you to recommend master Hooper to be more moderate in his behaviour; for he preaches four, or at least three times a day; and I am afraid lest these over abundant exertions should occasion a premature decay by which the very many souls now hungering after the very word of God, and whose hunger is well known from the frequent desire to hear him, will be deprived of both their teacher and his doctrine’. Anne Hooper to Henry Bullinger, April 3rd 1551 from Original Letters Relative to the English Reformation edited for the Parker Society by the Rev Hastings Robinson, the university Press MDCCCXLVI 1846. |

John 1:1 in the Tyndale Bible

Those Thats

Vic Perry

August 2003.

In 1526 Tyndale translated John 1:1, ‘In the begynnynge was that worde, and that worde was with god: and god was thatt worde.’ In 1534 this was changed to, ‘In the beginnynge was the worde, and the worde was with God: and the worde was God.’ The thats have gone. Neither Wycliffe, nor any translation after Tyndale inserts the three thats. The Geneva Bible of 1599 [DMH 247] followed by the Bishops’ Bible, has, ‘In the beginning was the Worde, and the Worde was with God, and that Worde was God’, but here ‘That Worde’ could refer back to the previously mentioned ‘Word’.

The thats are in 1526 Tyndale only. They are not in the Greek, and a recent book says that Tyndale was here ‘influenced by the Vulgate’, but the Vulgate has simply ‘In principio erat verbum’. And Erasmus’s parallel Latin version in his Novum Instrumentum, which Tyndale would have used, agrees with the Vulgate. However, Erasmus’s notes, in Evangelium Ioannis annotationes Erasmi Roterodami, may be the source of Tyndale’s thats. In his comments on John 1:1 Erasmus wrote `Verum illud propius ad hoc institutum pertinet, non simpliciter positum λόγος, sed additum articulum ὁ λόγος, ut non possit de quovis accipi verbo, sed de certo quoniam & insigni. Habet enim hanc vim articulus, quam latini utcunque redimus adiecto pronomine ille...’ He goes on to illustrate the par excellence use of the article in Greek, which in Latin could be indicated by the use of ille.

This suggestion is supported by the use of ille by other writers Pagninus, Piscator and Beza are referred to by Poole. Beza, for example, has in his chapter heading, ‘Sermo ille ante secula ex Deo genitus’; he translates the verse, ‘In principio erat Sermo ille, & Sermo ille erat apud Deum, eratque ille Sermo, Deus’; and he annotates, ‘Additus articulus excellentiam notat, discernitque hunc Sermonem, a mandatis divinis, quae alioqui sermo Dei dicuntur.’