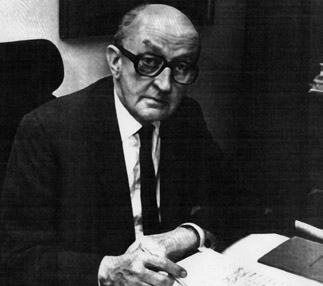

Sir Edward Pickering

Sir Edward Pickering, who died on 8 August 2003 aged 91, was the Founding Father of the Tyndale Society.

‘Pick of Fleet Street’ was a working journalist all his life. He was editor of the Daily Express when it achieved its highest sales (nearly four and a half million daily): he was pushed aside, but soon became chairman of Mirror Group Newspapers, and of the IPC newspapers and 70 magazines. He was later vice-chairman of the Press Council. For the last twenty years of his life he was an active executive vice-chairman of Times Newspapers Ltd.

Born and brought up in Middlesborough, he decided against university to go straight into journalism, starting as a reporter on the Northern Echo where, incidentally, he was sensational as a fortuitously successful racing correspondent. He was soon rising through posts on London papers. In 1939 he was chief sub-editor on the Daily Mail, a senior position held at the age of 27. His wartime experience in the Royal Artillery led, in 1944, to his demanding work (in rooms, he told me, in Senate House in the University of London), editing General Eisenhower’s daily communiqués before and after D-Day. In 1951 he joined the Daily Express. He created the most famous headline, across eight columns, for the Queen’s Coronation Day, as the news came in about Edmund Hillary and Sherpa Tenzing: ‘All This -- and Everest Too!’.

The problem with being editor of the Express was the irascible owner, Lord Beaverbrook, whose frequent rages were handled by ‘Pick’ with unruffled calm. Tantrums he met with a shrug: his disagreement was in a raised eyebrow, disapproval in a small smile. He would say, of dealing with outraged press barons, including Lord Harmsworth, ‘When you find yourself trapped in a cage with a tiger, you quickly learn in which direction to stroke his fur’. He inspired confidence in colleagues at all levels not only by his expertise in making newspapers, but also by his unflappability, perceptiveness, willingness to praise, and quietly effective methods of work over long hours.

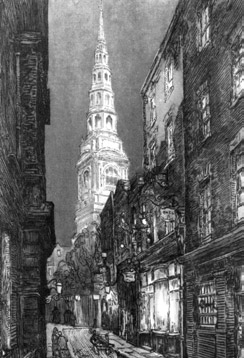

Honours came to him steadily. He was knighted in 1977. For his support of the Stationers’ and Newspaper Makers’ Company he was in 1985 made an Honorary Freeman and Liveryman, their highest award, and only the fifth made since 1945. His steady support for the journalists’ Wren church, St Bride’s in Fleet Street, included his office as Master of the Guild of St Bride.

Over several days in April 1992, I found rather baffling notes in my pigeonhole in the English Department at UCL, ‘Please ring Sir Edward Pickering’. When I was able to reach him, I heard for the first time that firm, modest, measured voice. He explained that the Guild of St Bride’s was wanting to celebrate the quincentenary of the birth of William Tyndale, but they were anxious to co-ordinate with other celebrations, and it was important that it should all happen at the same time. Could I tell him the accepted date of Tyndale’s birth? I could, and did. He invited me to lunch at the Garrick, one of his happiest haunts. Shortly after, he wrote the letter for The Times inviting interest and support, signed by Robert Runcie, Ted Hughes, Veronica Wedgwood, Phyllis James, Iris Murdoch and William Golding.

The letter was printed on 1 May 1992. The result was instant and soon almost overwhelming. Sir Edward arranged with Canon Oates, the Rector of St Bride’s, that a room could be used there for what he had founded as ‘The William Tyndale Quincentenary Trust’. This consisted of ‘Pick’ himself, Canon Oates, myself and, above all, Mrs Gillian Graham, to whom our profoundest thanks are always due. She, withdrawing from her fine work, much of it in Africa, for the Leonard Cheshire organisation, gave her full time to the new Trust, working voluntarily. The interest, more than nation-wide, especially for memorial services in 1994 on 6 October (Tyndale’s Day in the Anglican Prayer Book), grew and grew. There were special BBC programmes. Media coverage was outstanding. Developments were co-ordinated by Gillian Graham and eagerly watched by ‘Pick’. In London, everything culminated in a magnificent service in St Paul’s Cathedral attended by over a thousand people, addressed by Robert Runcie. ‘Pick’ later told his family that all this work had been one of the happiest things in his life.

He, of course, would not leave it there. So in January 1995 at an event at the British Library (then still in Bloomsbury), in most distinguished company, the Tyndale Society was launched. Over the years, Pick’s interest was deep. From his desk at The Times he followed everything we did, quite often telephoning me with suggestions. For nearly ten years he attended our UK conferences and lectures, coming to Oxford to the Hertford Tyndale lectures even when quite frail. He rejoiced at our steady expansion, and as we recently reached almost 400 members.

Two strokes unhappily limited his movements, but not his mind. He still went to his desk, and we spoke often. I had come to know his wife, Rosemary, and to understand her supreme importance in his life. I had heard at our first lunch that she was a very gifted singer, especially when accompanied on the piano by him: it was not until later that I began to understand their special happiness in performing Gershwin and Cole Porter, in private as well as in public.

Pick’s funeral at an overflowing St Bride’s on 20 August was moving. The first hymn was ‘O Jesus, I have promised’, the last ‘He who would valiant be’: that was led into by a reading from Pilgrim’s Progress, the account of the Crossing by Mr Valiant-for-truth which ends ‘and all the Trumpets sounded for him on the other side’ -- at which point three trumpets took us into Bunyan’s hymn. The address was given by his elder son, Aidan. He gave us personal details of ‘Ted’ (his other name among Fleet Street people), and communicated the love he had experienced.

Half a century ago, ‘Pick’ had spotted the potential in a young graduate of Worcester College, Oxford, named Rupert Murdoch. At the time, Lord Beaverbrook had remarked to ‘Pick’, about Murdoch, ‘Look after him. You never know where he might end up’ .The Memorial Service on 1 December, again at St Bride’s, included an address by Mr Murdoch, telling of the public career of ‘Ted’, with special private memories. These included the details that he knew Picasso well enough for the artist to inscribe a book for him with a personal drawing, and that he was the first Western editor to interview Khrushchev.

At his 90th birthday party, ‘Pick’ had said that he thought that he was too old now to retire. He never did. He was working from his bed the afternoon he died. His name, and his quiet, effective presence will live on in so many parts of public life, including, we rejoice to remember, the Tyndale Society itself. ‘Pick’ is already sorely missed. We in the Society maintain our thoughts and prayers for his widow Rosemary and their family, to whom we send our deepest sympathy, in what is their own, but also a national, loss.

David Daniell