When Tyndale was ordained in 1515 it is most unlikely that he foresaw the dramas that were to shake the very foundations of the church in the coming decades. The name of the German Augustinian friar Martin Luther had yet to become a term of abuse, applied indiscriminately to those the church came to consider as heretics and to be thrown at Tyndale in later years. However, by the time he was settled into his life at Little Sodbury the new 'heretical' ideas about theology and worship were circulating in Europe and in England. In 1521 Cardinal Wolsey attended at St. Paul's Cross, by the cathedral in the heart of London, and with great ceremony presided over a burning of Luther's writings. In the same year the king wrote against Luther for which he was to receive from Pope Leo X the title Defender of the Faith.

It is unclear at what point William Tyndale began to find his own thinking moving away in certain respects from the tradition of the church, nor do we know when he conceived the great vision of an English Bible. Certainly whilst he was at Little Sodbury, if not before, Tyndale was of the belief that the scriptures must be made available to the English people in their own language. At this point the Bible was read in church in Latin, the scholarly and ecclesiastical language of Europe, so meaning nothing to the average worshipper. Tyndale's single-minded pursuit of his objective determined so much of the remainder of his life. When he found himself in conflict with churchmen in Gloucestershire he decided upon a move to London in the hope that the bishop, Cuthbert Tunstall, would give him a position in his household to replace the patronage of John Walsh and so allow him to begin the translation of which he dreamed.

In this hope he was to be disappointed. However, shortly after arriving in London in 1523 he was approached by a London merchant who had heard him preach and who was obviously impressed by what he heard. Humphrey Monmouth gave Tyndale board and lodging in his house where the young scholar continued his studies 'lyke a good priest, studying bothe nyght and day'. Later Monmouth was to fall under suspicion as a result of his taking William Tyndale into his house for those six months.

Now in London Tyndale was in a good position to assess whether he might hope for any support in his work towards a Bible in English. As the months passed it became increasingly clear to him that the official attitude in England was, at the best, indifferent to such a project. The association of a Bible in the vulgar tongue with John Wyclif back in the fourteenth century and his followers, the Lollards, who were regarded as heretics, made for a more negative attitude towards translation in England than was commonly the case in mainland Europe. In 1524 Tyndale decided that pursuit of his goal might be best undertaken abroad and so he left London with a little financial backing from Monmouth and other sympathetic merchants.

© Brian Buxton 2013

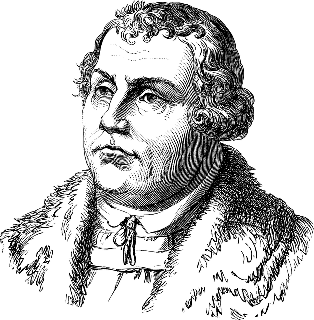

Portrait of Martin Luther

Portrait of Martin Luther